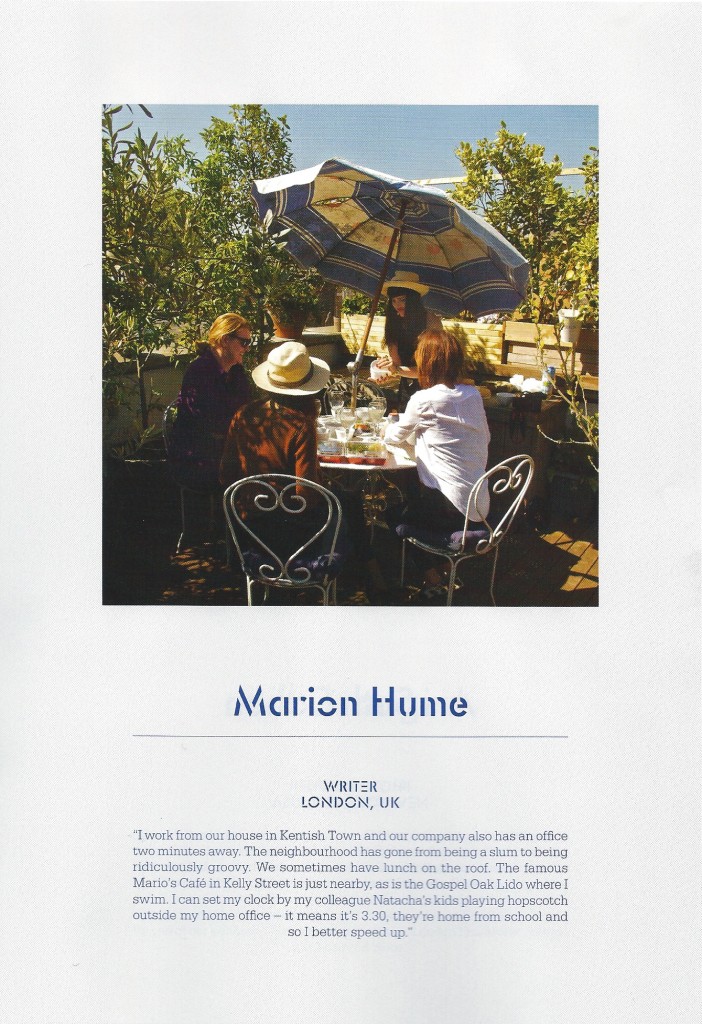

Marion featured in the August edition of Home Magazine in New Zealand, guest edited by Karen Walker.

Category Archives: People

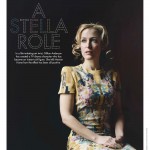

Stella Role – Sunday Life

Stella Role

In a life-imitating-art twist, Gillian Anderson has created a TV drama character who has become an instant cult figure. She tells Marion Hume how the effect has been all positive.

Sunday Life | October 2013

This really is bad form. I’m still sitting here, hours later than I expected, and Gillian Anderson, she of that gimlet stare and surly mouth, has no right to have made me feel so uncomfortable in my own skin – especially as she looks so supremely confident in hers.

It is 5am. I’m alone. I’ve just finished watching the complete series of the crime drama The Fall and there’s no way I can sleep now. So I’m sitting up, as the final credits roll, feeling jumpy and angry – the latter with myself, because I perched on this sofa hours ago, just for 10 minutes, to get a sense of the series and be prepped for meeting its lead.

I never intended to watch the whole thing in one sitting, but The Fall gets a grip on you. It’s compelling because it’s unexpected. It’s not “Scandi crime”, especially as Anderson’s character, Detective Superintendent Stella Gibson, wouldn’t be seen dead in a big ugly jumper. Instead, she is the centre of a universe into which men are invited, often for sex, then dismissed afterwards, followed by an expensive glass of pinot.

It is a mistake, of course, to confuse character with actor, yet Gillian Anderson so utterly inhabits her blisteringly intelligent and fiercely sexy detective that when the series ran on the BBC last June, it provoked an internet meme called “What would Stella do?” What Stella Gibson does when a male colleague comments on her seduction of a policeman is to fire back, “Woman subject, man object, it’s not so comfortable for you, is it?” and you can almost hear the sound of women around the world applauding. But what Stella says to an intrusive reporter is this: “No one knows better than me how important the media is … but really, you should f… off now.”

So it is with some trepidation that I set off to meet Gillian Anderson. She turns out to look rather unlike Stella, as she walks in wearing a floor-length, floral flutter of a sleeveless chiffon maxi dress accessorised by wedge sandals. Stella would be in something slippery, mean stilettos and the peek of a black lace bra.

Fashion, often not quite right on television, is pitch perfect in The Fall, where power dressing means satin in blush pink and a key scene hangs on a wardrobe malfunction at a police press conference. “It’s not fashion, it’s style,” Anderson corrects, relating how she and the costume team booked a VIP suite at a department store, then narrowed down Stella’s look from hundreds of separates hanging on the racks – no pant suits. When the series aired in the UK there was a marked spike in the sale of silk blouses.

We meet at London’s Young Vic theatre. Anderson has the looks of a beautiful woman whom the world thinks is gorgeous (“haughty lips”, “aquiline features”, “pellucid eyes” are among the more cerebral descriptions, while “sexiest woman alive” remains the favoured lads’ mag tag).

From what I have gleaned, Anderson has a reputation as a prickly interviewee – not surprising given she became famous as FBI Special Agent Dana Scully in The X-Files at the age of 24. Thus, at 45, she has spent more than two decades contractually obliged to promote her performances by chatting to the press. Having waded through clippings fatter than a police file, I find myself in sympathy – any sane human would be scratchy when asked, again and again, to reveal the truth about aliens, even though it is more than 10 years since Anderson left Scully behind and changed her hair from red to blonde.

After walking two steps behind David Duchovny’s Fox Mulder from 1993-2002 (although when she found out he was paid double she demanded, and got, wage parity) Anderson surely showed how sane she was by getting away from paranormal sightings in Vancouver and moving to Britain, where she spent the next decade garnering plaudits in television costume dramas such as Bleak House and Great Expectations. She also made movies (The Mighty Celt, Shadow Dancer) and turned down Lady Cora in Downton Abbey.

Today, she’s not prickly at all, instead passionate about The Fall and the relief that the role of DSI Gibson is making her known for being a grown woman – “although I’m not Stella by any stretch”. She senses, she says, her fame level rising again, as people snap pictures on public transport without asking (she takes the train and the London buses). Thankfully, this is nowhere close to what she had to deal with in her 20s, when the paparazzi rammed her car in order that, when she got out to get insurance details, they could grab their shots.

“I feel that Stella has had nothing but a positive effect on how I am in my life. Not to say there weren’t elements before, but I think she’s sharpened my sense of self and femininity,” says Anderson.

What of those feminist ripostes? “Well, I’ve always been the person most likely to say ‘f… off’,” she admits in her crystalline British accent (having spent part of her childhood in the UK, part in the US, she can switch seamlessly). “But the fact Stella is able to say ‘f… off’ with such poise brings her a different level of respect.” As for “What would Stella do?” becoming an online mantra to inspire other women, Anderson has had bumper stickers and fridge magnets made, with the proceeds going to a women’s shelter.

Adding to the mercurial unease of The Fall is its location in the still-scarred city of Belfast. DSI Gibson is the outsider, seconded from London’s Met because the Police Service of Northern Ireland has failed to catch a killer preying on young businesswomen. She does nothing to ingratiate herself.

The writing is whip-smart and female-friendly (although penned by a man, Allan Cubitt). “I think people expect me to be a lot more intelligent than I actually am, because I played Scully and now Gibson. But that’s not a bad thing,” says Anderson. “The majority of the women I’ve been blessed to inhabit are women who I’m flattered to have been able to spend time with, and for people to think I’m even remotely like them is great. Although there have been a few thrown in there that are less appealing,” she deadpans, perhaps referring to the intractable Lady Dedlock and the flinty Miss Havisham.

What’s novel – though it shouldn’t be – is the capacity for female friendship that ripples through The Fall. “That’s really important,” says Anderson, fire-flashing those pale sapphire eyes, “to show adult, mature women – completely different in the experiences they’d been through and the choices that they’d made – bonding through womanhood. Too often, what is portrayed between women is either ‘girly’ and going shopping, or the opposite, the negativity.”

In the show, a female detective and forensic scientist discuss how they balance the dead bodies at work with live ones at home, talking of “doubling”, “compartmentalising”. “I compartmentalise everything,” says Anderson. “It’s useful in the work that I do, but it can be very separating in my personal life.”

That life cannot be entirely personal, given Anderson was thrust into the spotlight virtually straight out of drama school. Then she proved catnip to the tabloids by having her first child, Piper, as the first series of The X-Files reached a cliffhanger close. She married a Canadian, gave birth, returned to work 10 days later, got divorced, married again, divorced, had her sons, now aged seven and five, within a now-defunct long-term partnership – Anderson’s whole adult arc has been documented. Plus, she’s peppered it with all manner of juicy details (“‘I’ve experimented with women’ – X-Files star confesses to lesbian flings”, The Daily Mail) because she does interviews alone, including this one, with no publicist hovering to keep things on message. In high school she was voted “Most Bizarre” and “Most Likely to Be Arrested”.

She says her own judgment has matured, that she sees people beyond the pigeonholes she once put them in. “Human beings are so much more complicated than we often give them credit for. We see someone on the bus and we put them in a box. Then you discover that, actually, that person has been sexting with half of the world – all of that kind of stuff, it’s shocking!” she laughs. As for those buses, “If it gets too intense, I’m pretty good at putting up a wall of ‘Do not stare’. I actually find that, when I’m in America, I’m much more open. I behave more American, and I am more likely to go, ‘Hey, yeah, take a photo.’ I’m much more guarded here, but that’s because I think I’m much more British here.”

Maybe I’m being terribly British because I find I have no desire to ask Anderson if she’s dating or how her young-adult daughter is fairing or how she juggles work as a single mum with two little boys at home. But then I realise this isn’t about nationality, it’s about professional respect. As we talk about her ambitions, about Stella’s wider role as a representation of 21st-century middle-aged womanhood, we are businesslike. Because, after all, acting is Anderson’s business and her accomplishments are evident. And I have entirely forgiven her for my sleepless night.

The Fall starts on BBC UKTV on Foxtel on October 19.

Riding The Coat Tales – The Australian Financial Review

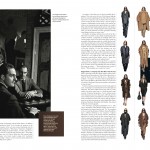

Riding The Coat Tales

Luigi Maramotti has strong views on many things, from a distaste for star designer egos, to resisting the ghettoism of fashion, to cheese. The chairman of the Italian cost company Max Mara shows Marion Hume around the company’s small-town headquarters.

The Austalian Financial Review | September 2013

Reggio Emilia, some two hours east of Milan, is renowned for cheese and for coats. The first has the longer history; rich pastures and traditions being behind wheels of salty treasure that have little in common with ready-grated so-called parmesan found at the supermarket. The family behind the coats remains involved in the making of Parmigiano Reggiano too; both requiring skill and time to achieve the sublime. The label on the coats is Max Mara.

“The fabric we use has been left to lie – the whole idea of seasoning the fabric like you do for a cheese – it’s very slow,” says Luigi Maramotti, a man of quiet yet intense passion who is the company chairman (and who also owns a farm). “A lot of people don’t even know that, at the price per ounce, they might even be paying more for a daily cheese than for the best cheese in the world!”

Is it odd that the head of a fashion powerhouse worth some US$1.7bn should be talking – and with some ferocity – about cheese? Maramotti, a long cool drink of water, also holds strong opinions about high speed rail, education, the “greenwashing” that allows big companies to play at being ethical, as well as the challenges of finding artisans at a time of rising unemployment and austerity yet youthful obsession with being a star. He is also absolutely passionate about art (is that a Gerhard Richter to his left?) and is impeccably attired in a beautiful suit.

Handmade where? Max Mara doesn’t do menswear; the brand celebrates the marriage of technology and the human hand in 23 different womenswear labels. So he brushes the question of the provenance of his suit away, instead indicating what he considers perfection. “These chairs,” he gestures, “designed in 1956, finding the perfect balance, it works, still, but it is not obvious, you need the time, the know-how. ‘Classic’ can have newness and excitement, but perhaps not at a glance….”

At a glance, a Max Mara coat is always beautifully fit-for-purpose. That coats are at the core might go some way to explain why the Max Mara Group has been slow to expand in Australia (while Australia is a luxury source of the merino in so many of those coats…). “I’m not trying to compare to Michelangelo and the quality of the marble, but when you see some great merino, great cashmere or a modern fabric with steel inside which keeps the memory of the shape, it is important,” says Maramotti. “Design being born from respect of the fabric, you do the minimum, you don’t over-design. Shouting about design is not how we convey value.”

No hoopla, no designer taking a bow. Each of the Max Mara lines is created by a team, usually comprising long-term company loyalists, a peppering of emerging talent from London design schools with which Max Mara Group has strong links ( and who, mostly, stay a while, then flee small town life) plus big names such as Karl Lagerfeld; Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana; the Roman, Giambattista Valli and from America, Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez of Proenza Schouler. Yet the latter are only acknowledged when they are no longer working for the company. What is the logic of that? Maramotti says that naming them would only build a platform for their egos, “because it is very unlikely they will negate their ego(s)”. Anonymity instead allows fashion stars to, “forge their expertise with ours and that of our technical teams. I accept that, today, there is a common advantage to use the designer as a marketing tool by which you go for a creative vision of an individual who wants to impose that vision on women….” his mouth forms into a moue of distaste. “What underpins us is a respect for women”.

Reggio Emilia is a company town – Max Mara owns the local hotel, a restaurant and many locals drive or bus to work at the nearby Max Mara campus of steel, glass and several thousand trees. But this is not – Maramotti is emphatic – an outpost. “I measure using not geography, but time. There is a beautiful station near here, designed by (Valencian star-chitect) Santiago Calatrava. I can be in Milan in 38 minutes. How far can you travel in London in 38 minutes? My point is centrality or decentrality is a state of mind…”

Certainly, this has to be the world capital of coats. A morning tour of production has been thorough and impressive. The classic 101801 (known since 1981 by a code number, no catchy names here) is a double-breasted camel overcoat of balanced proportions. A navy cashmere parka with voluminous hood, new this season, will look great for years. In other factories, presumably just as hi-tech, millions of items of clothing for women who want to look up with the times, but not up to the minute, are also made and labeled Max Mara, Sportmax, Pianoforte, Pennyblack, Marella, these joined by Max&Co.,for teenage girls.

The current chairman’s great, great grandmother was a 19th century dress maker called Marina Rinaldi, who has had a label named in her honour since the early 70s. “In everything we do, we resist the ghettoism of fashion. Marina Rinaldi has kept a different thinking in our company,” explains Maramotti, this referring to the welcome fact that Marina Rinaldi is a fashionable alternative for curvier, bustier or taller women who do not otherwise appreciate being siloed into a swamp called“plus sized”. Instead, Marina Rinaldi has seasonal collections, stores on London’s Bond Street, Avenue Montaigne in Paris, a Sydney store in Chifley Plaza. “It is politically correct to say size is not an issue yet size in fashion, it’s a kind of a taboo,” says Maramotti. “I’ve met many women in my life who are interesting and at peace with themselves and not a tiny size.”

Time to get personal. Much of my own wardrobe is Marina Rinaldi – expensive yes, long-lasting too. While of course I don’t believe you have to fit the clothes to write about them (then where would I be?) in a rare subjective assessment, I can confirm that white linen pants last for summers, navy wool tunics can go anywhere and T-shirts keep their shape. My challenge is sometimes I haven’t been able to keep my clothes. I haven’t misplaced any of them, I know exactly why they do not return from hotel laundries. I recall a hotel manager, a big boned woman, offering free nights to compensate my “loss” (her gain). As you don’t need many clothes on an island and I had time to spare, both parties were delighted. I have other examples – enough to argue that larger women love great clothes if they can get their hands on them, but enough for now.

When the founder of the Max Mara Group, Achille Maramotti, died in 2005, he left a business in the care of his three children, Luigi, Maria Ludovica (in charge of product development) and Ignazio (managing director) and this has always been a generational, family story (the company remains private and family controlled). Achille started in 1951, in that post-war surge that saw Northern Italy transforming from an agricultural to an industrial economy. He was much inspired by the female force in his life, his mother, Giulia Fontanesi Maramotti, who, widowed since 1939, had raised four children, funded by her dressmaking school where other young women could gain skills to ensure their independent survival. Achille took a law degree, funded by several jobs including working in a raincoat factory in Switzerland, where he realised that his mother’s craft could be industrialized through a logical system of work. Degree done, he got started, offering useful, attractive clothes to women who had neither the need nor the capital for copies of coquettish Parisian haute couture. The rise of Max Mara is one of classic capitalism, of a man driven by need plus a vision; that creativity could be harnessed profitably to technology. Achille travelled to America where clothes meant the garment industry not a local dressmaker. By the dawn of the 60s, Max Mara production was streamlined to the point that a coat that had taking 18 hours required only two. The company remains is a triumph of technology plus the skills of the human brain and hand (no machine can secure buttons as well as a person can). “Technology helps people repeat best performance for the entire day,” explains Luigi Maramotti. “ Handmade is another legend. It is not true handmade is better than machine. Machines help human beings be the best – you need both. The future, yet the know-how not forgotten.”

Yet the know-how seemingly inherent in the “Made in Italy” label has become complex. “It is a slogan… this idea of democratization of fashion comes from Italy, absolutely. Yet ‘Made in Italy’ can be very frustrating,” Maramotti says, refering to the fact that all one needs to do is put the pieces together in Italy for a garment to earn the prized ‘Made In Italy’ label. “Yet if I design it here, I do prototypes here; that doesn’t count. The central point is, are we, in Italy, capable of keeping alive a heritage that goes back centuries, to the Renaissance, the workshops for ideas?” Another challenge is manning those workshops (with women, the majority of employees). About 20 people in Reggio Emilia retire or relocate each year yet as Italy stumbles through recession, there is no line at the factory gates, despite The Max Mara Group working with the Italian public sector to fund skills training. “This becomes anthropological,” Maramotti muses of the paradox of high unemployment and the lack of apprentices or skilled workers. “You see a lot of young people dreaming of doing things that are much less relevant which they think are better. The values are not perceived correctly. We fight against the perception of ‘blue collar’. I don’t think the major issue is the salary.”

Hardly a casual chat this, for the next subject is sustainability, Maramotti being no fan of external pressures applied by advocacy groups. “There is an entire marketing on these ethical balance sheets,” he sniffs. “I have always opposed this because I prefer to do what works for us. Our power comes from hydro energy, but you don’t make a manifesto, you do the right thing, full stop. The moment it becomes a marketing tool, you are doing something that, ethically, is debatable. I prefer coherence. I know that coherence is boring. Consistency is boring too. But that is the case here.” He warms to the theme, “Some people see a society in which consumption is reduced to a minimum. But because I was trained to look at creativity as part of the growth of an individual, this vision of reducing consumption, making nothing, it is, in a way, offensive to the human intellect. So we have to find a way where we don’t kill ourselves with a model which is sterile.”

Of his own role, of the boss who inherited the top job, he is thoughtful too. “Never separate privileges from burdens, you are just born there, and you have to take what that means,” he muses. “The point is, what are you going to do with that? Absolutely I am privileged. I can think, I can do things. Does that bring responsibility and burdens? That is the question.”

All That Baz – The Telegraph

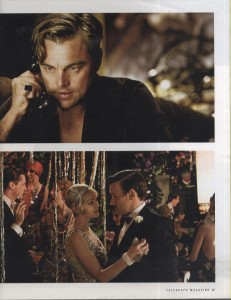

All That Baz

A new film of The Great Gatsby recreates the glamour and decadence of the Prohibition era. Marion Hume meets the director Baz Luhrmann on the set, where — as in the novel — reality and illusion collide.

The Telegraph | April 2013

The Great Gatsby is a slender book. Yet you can be certain of a sweeping epic of a film in May. In F Scott Fitzgerald’s introspective novel, every utterance is weighed. This is not how things work in the world of Baz Luhrmann. You don’t even get through the question, ‘When did you first read the…’ before the 50-year-old director who brought us Strictly Ballroom, Romeo + Juliet and Australia is in full flow.

‘I was on my break after making Moulin Rouge, on the Trans-Siberian, and I don’t want to bag out Mongolia, but it was a bit lonely and that’s when I decided, I have to read The Great Gatsby. It was unbelievable! This was written when jazz was around and parents were arresting their children and putting them in court because they were so out of control. The orgy of money and booze! Only yesterday women were wearing hems down to their ankles and now they were wearing underwear as clothing!’

This, in Luhrmann-land (a magical place to be), counts as a short soundbite. Just as he makes films that seem to draw their megawatt dazzle straight off the mains, so does Luhrmann himself seem powered by an extraordinary voltage.

We are meeting in a mansion on the East Coast of the United States, where a wild party is in full swing, the bandmaster is spinning like a top and louche ladies are lounging on lilos shaped like floating zebras in a floodlit swimming pool. Beyond the garden, stumbling stragglers are enjoying their own inebriated merriment down on the beach. Way out in the distance a green landing light blinks from a dock. ‘What is Gatsby? What is a gangster? Who’s good? Who’s bad? Once you realise that everyone’s living a bit of a lie, then everyone finds it easier to live a very big lie. This…’ Luhrmann says with a vast sweep, ‘is the Prohibition. Just look at those bottles of Moët!’

While the Moët is the real McCoy, we are not, of course, at Jay Gatsby’s sumptuous home. Actually, we’re not even in America, but in Sydney, on one of the biggest sound stages in the world. A few miles across town, smack in the centre of one of the grittiest inner-city neighbourhoods, stands a real mansion (rather than one of putty and paint), called Iona, the headquarters of the global empire that is Bazmark Films. There, alongside those involved with Gatsby, another team is working on the live stage show of Strictly Ballroom, the 1992 film with which Luhrmann did nothing short of change the way more than 40 nations watch Saturday night television. It’s true – the BBC’s Strictly Come Dancing (and Dancing with the Stars, as it is known in other markets) was inspired by his love story of a gallumphing girl transformed in the arms of her dance partner.

‘A life lived in fear is a life half-lived,’ was the mantra of that film, which marked its then 29-year-old Australian director as one to watch. It remains the motto of Bazmark, and certainly taking on Gatsby is the act of a fearless man. To Americans it is something of a sacred text: it has been filmed five times before (as a silent movie in 1926; in 1949 starring Alan Ladd; most lusciously with Robert Redford in the lead role in a 1974 version with a script by Francis Ford Coppola; it was filmed for television in 2000 and again, with a modern twist, as G in 2002). Adding to that, Luhrmann is amping up the sexual tension to a hip-hop soundtrack by Jay-Z, and he is filming in 3D.

‘I just hope that we open the door to a new generation and we tell the story well,’ he says. ‘3D allows you to see awesome actors in the prime of their career going at each other. For me, it’s about watching actors act.’ He pauses. ‘The special effects look pretty good, too!’

The Great Gatsby follows a young Midwesterner, Nick Carraway (played by Tobey Maguire), as he arrives in Manhattan in the wild spring of 1922, at a time when the bond market is rocketing, bootleggers are thriving and morals are loosening. He rents a house in Long Island, next to the mansion of a mysterious new-money millionaire, Jay Gatsby (Leonardo DiCaprio), and across the water from the old-moneyed – and unfaithful – Tom Buchanan (Joel Edgerton), married to Carraway’s cousin Daisy (Carey Mulligan). He quickly gets caught up in a world of arrogant privilege and bears witness to its tragic consequences.

To the edge of the party stands the host. On cue he turns to face the camera. ‘I’m Jay Gatsby. I’m sorry, Old Sport, I thought that you knew that,’ DiCaprio says to Tobey Maguire. The pair do take after take. To keep things fresh, Maguire starts feeding deviations on the script to his friend, but with 3D, every possible camera angle is covered, and rudimentary lip-reading reveals his ad libs are rude. (‘Ah,’ Maguire says, chastened, when we meet later, ‘you saw?’) Yet DiCaprio is flawless. He turns, dazzles, holds a beat, then says again, ‘I’m Jay Gatsby.’

The subtitle of the novel, written in 1925, was ‘The tale of a man who built himself an illusion to live by’. As an actor DiCaprio has proved himself a master of the illusion that is movie-making, ever since, as an already-seasoned performer of 18, he almost stole What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? from Johnny Depp. DiCaprio has since become a screen star so consistently outstanding (he has been nominated three times for an Academy Award, for Gilbert Grape, Blood Diamond and The Aviator) that it is beginning to look like bad manners that he has never received an Oscar.

As we learn in the novel, Gatsby, born James Gatz, is a poor boy who has willed himself wealthy to get the girl he has always loved, and is now the subject of endless speculation. In fiction, strangers trade Gatsby stories; outside in the long, hot Australian summer of filming, it is ‘Leo’ who is the fodder. Girls hold vigil where he is alleged to be staying. If he appears in public, there’s a feeding frenzy; if he doesn’t, the paparazzi seek him here, seek him there, perhaps egged on by some sense of entitlement – of a film budget rumoured to be AU$120 million (£82 million), some $50 million is being funded, indirectly, by the Australian public in the form of tax concessions.

Even my silver-haired aunt has a Leo story. Her dreadlocked surfer-dude handyman disappears for weeks, only to come back looking as sleek as an otter because he has landed the job of Leo’s body double. This proves a useful barometer for gauging if the star is on set or has left town: when DiCaprio, a committed environmentalist, headed off to visit the widow of the Crocodile Man, Steve Irwin, Auntie Jean got her lawn mown.

On set, too, it is DiCaprio about whom everyone is curious. Very few international reporters have been allowed access. ‘I wonder if we’ll meet Leo?’ the reporter from Munich whispers. ‘I hope so!’ swoons the one from Spain. Yet as we walk between sound stages, DiCaprio, who, unusually for a film star, is far taller than you’d expect, walks directly towards us. He neither evades nor engages. Extraordinarily, only two of us even register that it is him.

When a novel is loved, the challenge is to make a retelling sizzle. The executive producer, Doug Wick, secured the rights for Luhrmann, who, he believes, will make a story so many people know by heart feel fresh once more. ‘If a young person sees this, they better think it’s a cool party. Baz knows how to throw a party,’ Wick says.

Luhrmann’s given name of Mark was ditched not long after he left Herons Creek, a dot on the map of New South Wales where his father ran the petrol station and the cinema. The boy became the man who maintains an Outback-scaled theatricality. When Baz and his costume and production designer wife, Catherine Martin, married on the stage of the Sydney Opera House in 1997, legend has it that the celebrant descended by zip wire.

An Australian in a beanie hat shuffles up. Joel Edgerton snared the role of the entitled and athletic Tom Buchanan after Ben Affleck pulled out when his passion project Argo got the green light. When Edgerton (recently seen in Zero Dark Thirty) met Luhrmann the director gave him a copy of the book. ‘I’ve never been a big reader in my life. I don’t hold books as precious as a lot of other people do,’ Edgerton says. ‘I dropped it into my bag and went to meet a friend and I was like, “Baz gave me a copy of the book,” and my mate said, “Give me a look at that.” And it was a very, very special copy, which I didn’t understand all that much – you know, when books are printed and what edition they are – and then I felt terrible that I’d shown such ignorance or arrogance.’

Edgerton must project both – as well as the faintest hint of a heart – in the role of a hard-muscled, flinty, white supremacist whose other girl is Myrtle Wilson (played by a fellow-Australian, Isla Fisher), the blousy bride of a garage mechanic. ‘Tom’s socio-economic background is different from mine, although I do plan one day to be as rich as Tom Buchanan,’ Edgerton says, laughing. ‘Working with Baz, he’s basically Wikipedia. He provides you with all the doors and rooms and avenues and pathways to understand the world from etiquette to language to design to everything else.’

Edgerton (of Bankstown, NSW, far removed from posh) has grasped the differences between old money and new wealth. ‘Have you seen my house yet? Make sure you wipe your feet. My house is like the White House. Gatsby’s house is like Disneyland, all about the glitz and glamour, and mine’s all elegant and pure. And then Myrtle’s apartment is like my Nana’s been decorating. On crack. It’s the tackiest little apartment you’ve ever seen. Yes, Tom likes shagging her, but every time he walks in he looks around and goes, “Oh, God, not another ornament.”’

Outside on the lawn, where the air is heady with the scent of roses, a lithe girl in an oyster satin trouser suit is casually swinging a strand of pearls. ‘I have some beautiful rings, too,’ she says, extending her hand by way of a hello. The character is Jordan Baker, a golf pro who has an affair with Carraway; the actress is Elizabeth Debicki, an ingenue straight from drama school. ‘Baz saw me and he asked me,’ she explains with Jordan-like nonchalance.

Scott Fitzgerald was a customer of Tiffany & Co, the most famous jeweller of the Jazz Age. Thus despite it being highly unusual and fraught with risk to use real gems on a film set, Catherine Martin spent months working with the company to reissue a few original 1920s designs and to come up with others with an Art Deco feel. ‘There’s something about knowing that they’re incredibly expensive. It makes you move your hands differently,’ Debicki says.

While the rest of the little press posse goes back to Gatsby’s house, I sneak off to meet Charlie – no other name is given, and when I notice his muscles, I dare not ask. After the double-locked doors, past the CCTV cameras, Charlie opens a safe like a pro, slips on black cotton gloves and starts opening Tiffany-blue boxes. ‘See here, Daisy got this when she was a little girl,’ he says, cradling a silver locket in his enormous hand. I’m rather more taken by what Daisy gets as a grown-up. There’s an exquisite bejewelled brace of feathers on a plaster-pink ribbon. ‘It sits, like this, on her head,’ Charlie says, demonstrating on himself, somewhat incongruously. ‘It is in what will become a famous scene, where she’s standing in the sun, looks across and sees Gatsby.’

Two days later I return to catch up with Catherine Martin. It is now December 22, steaming hot outside and tense indoors because everything must wrap by lunchtime if Carey Mulligan is to make it back to England for Christmas Eve. ‘Fine jewellery is called fine jewellery for a reason,’ Martin starts. ‘Case in point: Daisy’s headpiece. It’s an archival piece that was made in the late teens. And I thought that was perfect, it could almost have belonged to her mother and then she gets it. It has been remade by Tiffany, but we also use genuine pieces.’

One of these is a jabot pin carved from rock crystal embellished with onyx and diamonds. It is among Tiffany & Co’s most treasured artifacts, and it is Charlie’s main job to protect it. Yet when Jordan Baker meets Nick Carraway she shows off the precious pin stuck casually into her hat. Among the many pieces that have been created specially for the film are cufflinks, a signet ring and the silver handle of a cane, each of which carries Gatsby’s monogram of a daisy, his permanent aide memoire for the reason he is so passionate about the trappings of wealth: because he believes the girl he loves requires them.

Martin’s unbreakable rule has been, ‘Never one feather only. This is not a flapper-themed 21st-birthday party. My aim,’ she says, ‘is to express the true nature of the period through an eclectic combination of things that have a real point of reference.’

This does not mean that she is a stickler for historical accuracy. Part of Martin’s genius (she has won two Oscars, after all, one as production designer, the other as costume designer, both for Moulin Rouge) is how she mixes modern pieces that reference the past in order to make that past seem current. ‘You can’t live your life in fear of the fashion police,’ she says as we flick through racks of delicious dresses by Prada.

‘You have to do what’s right to tell the story and what you believe makes an ethereal moment.’ Like those inflatable zebras in the pool, I say, thinking back to how the eye-popping stripes added even more verve to the party scene. She stops in her tracks. ‘Leonardo was saying to me the other day, “Those zebra lilos didn’t exist,” and I said, “Yes, I have a picture of them.” Here it is.’ (I take the photocopy, glad that Leo and I have at least connected somehow.)

As I leave, I spy Carey Mulligan, slumped on a chair as her final scene is set up, wearing a breathtaking crystal-encrusted Prada party dress with a hideous pair of Crocs. The clock is ticking. I ask her if the Tiffany rock on her finger has helped her to ‘find’ the flighty, beautiful Daisy? ‘I do find myself staring at her ring,’ she replies. ‘I mean, I would never spend more than £100. I would never in a million years imagine actually owning this, so it does throw you into that world. Have you met Charlie who follows me around? The whole notion of Tom and Daisy is that Tom seduces her and wraps her in jewellery. He contains her with his money. They have become a couple because she wanted a great sense of wealth and superiority and he ensnared her with these things.’ She twirls the ring on her slender finger. ‘You feel the weight. In the scenes between Daisy and Gatsby, the engagement ring Tom gave her becomes such a weighty thing.’

In the end, Mulligan will catch her plane. DiCaprio will leave town and my aunt will once again have a gorgeous garden. ‘So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past,’ is how Scott Fitzgerald ended his finest work. As to how Luhrmann ends what promises to be his – and does so in 3D – remains a mystery until next month.

The Great Gatsby is out on May 16. Tiffany’s Ziegfeld Collection celebrates the company’s collaboration with Warner Bros and Bazmark Films on The Great Gatsby (