We are meeting in a mansion on the East Coast of the United States, where a wild party is in full swing, the bandmaster is spinning like a top and louche ladies are lounging on lilos shaped like floating zebras in a floodlit swimming pool. Beyond the garden, stumbling stragglers are enjoying their own inebriated merriment down on the beach. Way out in the distance a green landing light blinks from a dock. ‘What is Gatsby? What is a gangster? Who’s good? Who’s bad? Once you realise that everyone’s living a bit of a lie, then everyone finds it easier to live a very big lie. This…’ Luhrmann says with a vast sweep, ‘is the Prohibition. Just look at those bottles of Moët!’

While the Moët is the real McCoy, we are not, of course, at Jay Gatsby’s sumptuous home. Actually, we’re not even in America, but in Sydney, on one of the biggest sound stages in the world. A few miles across town, smack in the centre of one of the grittiest inner-city neighbourhoods, stands a real mansion (rather than one of putty and paint), called Iona, the headquarters of the global empire that is Bazmark Films. There, alongside those involved with Gatsby, another team is working on the live stage show of Strictly Ballroom, the 1992 film with which Luhrmann did nothing short of change the way more than 40 nations watch Saturday night television. It’s true – the BBC’s Strictly Come Dancing (and Dancing with the Stars, as it is known in other markets) was inspired by his love story of a gallumphing girl transformed in the arms of her dance partner.

‘A life lived in fear is a life half-lived,’ was the mantra of that film, which marked its then 29-year-old Australian director as one to watch. It remains the motto of Bazmark, and certainly taking on Gatsby is the act of a fearless man. To Americans it is something of a sacred text: it has been filmed five times before (as a silent movie in 1926; in 1949 starring Alan Ladd; most lusciously with Robert Redford in the lead role in a 1974 version with a script by Francis Ford Coppola; it was filmed for television in 2000 and again, with a modern twist, as G in 2002). Adding to that, Luhrmann is amping up the sexual tension to a hip-hop soundtrack by Jay-Z, and he is filming in 3D.

‘I just hope that we open the door to a new generation and we tell the story well,’ he says. ‘3D allows you to see awesome actors in the prime of their career going at each other. For me, it’s about watching actors act.’ He pauses. ‘The special effects look pretty good, too!’

The Great Gatsby follows a young Midwesterner, Nick Carraway (played by Tobey Maguire), as he arrives in Manhattan in the wild spring of 1922, at a time when the bond market is rocketing, bootleggers are thriving and morals are loosening. He rents a house in Long Island, next to the mansion of a mysterious new-money millionaire, Jay Gatsby (Leonardo DiCaprio), and across the water from the old-moneyed – and unfaithful – Tom Buchanan (Joel Edgerton), married to Carraway’s cousin Daisy (Carey Mulligan). He quickly gets caught up in a world of arrogant privilege and bears witness to its tragic consequences.

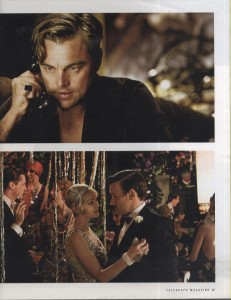

To the edge of the party stands the host. On cue he turns to face the camera. ‘I’m Jay Gatsby. I’m sorry, Old Sport, I thought that you knew that,’ DiCaprio says to Tobey Maguire. The pair do take after take. To keep things fresh, Maguire starts feeding deviations on the script to his friend, but with 3D, every possible camera angle is covered, and rudimentary lip-reading reveals his ad libs are rude. (‘Ah,’ Maguire says, chastened, when we meet later, ‘you saw?’) Yet DiCaprio is flawless. He turns, dazzles, holds a beat, then says again, ‘I’m Jay Gatsby.’

The subtitle of the novel, written in 1925, was ‘The tale of a man who built himself an illusion to live by’. As an actor DiCaprio has proved himself a master of the illusion that is movie-making, ever since, as an already-seasoned performer of 18, he almost stole What’s Eating Gilbert Grape? from Johnny Depp. DiCaprio has since become a screen star so consistently outstanding (he has been nominated three times for an Academy Award, for Gilbert Grape, Blood Diamond and The Aviator) that it is beginning to look like bad manners that he has never received an Oscar.

As we learn in the novel, Gatsby, born James Gatz, is a poor boy who has willed himself wealthy to get the girl he has always loved, and is now the subject of endless speculation. In fiction, strangers trade Gatsby stories; outside in the long, hot Australian summer of filming, it is ‘Leo’ who is the fodder. Girls hold vigil where he is alleged to be staying. If he appears in public, there’s a feeding frenzy; if he doesn’t, the paparazzi seek him here, seek him there, perhaps egged on by some sense of entitlement – of a film budget rumoured to be AU$120 million (£82 million), some $50 million is being funded, indirectly, by the Australian public in the form of tax concessions.

Even my silver-haired aunt has a Leo story. Her dreadlocked surfer-dude handyman disappears for weeks, only to come back looking as sleek as an otter because he has landed the job of Leo’s body double. This proves a useful barometer for gauging if the star is on set or has left town: when DiCaprio, a committed environmentalist, headed off to visit the widow of the Crocodile Man, Steve Irwin, Auntie Jean got her lawn mown.

On set, too, it is DiCaprio about whom everyone is curious. Very few international reporters have been allowed access. ‘I wonder if we’ll meet Leo?’ the reporter from Munich whispers. ‘I hope so!’ swoons the one from Spain. Yet as we walk between sound stages, DiCaprio, who, unusually for a film star, is far taller than you’d expect, walks directly towards us. He neither evades nor engages. Extraordinarily, only two of us even register that it is him.

When a novel is loved, the challenge is to make a retelling sizzle. The executive producer, Doug Wick, secured the rights for Luhrmann, who, he believes, will make a story so many people know by heart feel fresh once more. ‘If a young person sees this, they better think it’s a cool party. Baz knows how to throw a party,’ Wick says.

Luhrmann’s given name of Mark was ditched not long after he left Herons Creek, a dot on the map of New South Wales where his father ran the petrol station and the cinema. The boy became the man who maintains an Outback-scaled theatricality. When Baz and his costume and production designer wife, Catherine Martin, married on the stage of the Sydney Opera House in 1997, legend has it that the celebrant descended by zip wire.

An Australian in a beanie hat shuffles up. Joel Edgerton snared the role of the entitled and athletic Tom Buchanan after Ben Affleck pulled out when his passion project Argo got the green light. When Edgerton (recently seen in Zero Dark Thirty) met Luhrmann the director gave him a copy of the book. ‘I’ve never been a big reader in my life. I don’t hold books as precious as a lot of other people do,’ Edgerton says. ‘I dropped it into my bag and went to meet a friend and I was like, “Baz gave me a copy of the book,” and my mate said, “Give me a look at that.” And it was a very, very special copy, which I didn’t understand all that much – you know, when books are printed and what edition they are – and then I felt terrible that I’d shown such ignorance or arrogance.’

Edgerton must project both – as well as the faintest hint of a heart – in the role of a hard-muscled, flinty, white supremacist whose other girl is Myrtle Wilson (played by a fellow-Australian, Isla Fisher), the blousy bride of a garage mechanic. ‘Tom’s socio-economic background is different from mine, although I do plan one day to be as rich as Tom Buchanan,’ Edgerton says, laughing. ‘Working with Baz, he’s basically Wikipedia. He provides you with all the doors and rooms and avenues and pathways to understand the world from etiquette to language to design to everything else.’

Edgerton (of Bankstown, NSW, far removed from posh) has grasped the differences between old money and new wealth. ‘Have you seen my house yet? Make sure you wipe your feet. My house is like the White House. Gatsby’s house is like Disneyland, all about the glitz and glamour, and mine’s all elegant and pure. And then Myrtle’s apartment is like my Nana’s been decorating. On crack. It’s the tackiest little apartment you’ve ever seen. Yes, Tom likes shagging her, but every time he walks in he looks around and goes, “Oh, God, not another ornament.”’

Outside on the lawn, where the air is heady with the scent of roses, a lithe girl in an oyster satin trouser suit is casually swinging a strand of pearls. ‘I have some beautiful rings, too,’ she says, extending her hand by way of a hello. The character is Jordan Baker, a golf pro who has an affair with Carraway; the actress is Elizabeth Debicki, an ingenue straight from drama school. ‘Baz saw me and he asked me,’ she explains with Jordan-like nonchalance.

Scott Fitzgerald was a customer of Tiffany & Co, the most famous jeweller of the Jazz Age. Thus despite it being highly unusual and fraught with risk to use real gems on a film set, Catherine Martin spent months working with the company to reissue a few original 1920s designs and to come up with others with an Art Deco feel. ‘There’s something about knowing that they’re incredibly expensive. It makes you move your hands differently,’ Debicki says.

While the rest of the little press posse goes back to Gatsby’s house, I sneak off to meet Charlie – no other name is given, and when I notice his muscles, I dare not ask. After the double-locked doors, past the CCTV cameras, Charlie opens a safe like a pro, slips on black cotton gloves and starts opening Tiffany-blue boxes. ‘See here, Daisy got this when she was a little girl,’ he says, cradling a silver locket in his enormous hand. I’m rather more taken by what Daisy gets as a grown-up. There’s an exquisite bejewelled brace of feathers on a plaster-pink ribbon. ‘It sits, like this, on her head,’ Charlie says, demonstrating on himself, somewhat incongruously. ‘It is in what will become a famous scene, where she’s standing in the sun, looks across and sees Gatsby.’

Two days later I return to catch up with Catherine Martin. It is now December 22, steaming hot outside and tense indoors because everything must wrap by lunchtime if Carey Mulligan is to make it back to England for Christmas Eve. ‘Fine jewellery is called fine jewellery for a reason,’ Martin starts. ‘Case in point: Daisy’s headpiece. It’s an archival piece that was made in the late teens. And I thought that was perfect, it could almost have belonged to her mother and then she gets it. It has been remade by Tiffany, but we also use genuine pieces.’

One of these is a jabot pin carved from rock crystal embellished with onyx and diamonds. It is among Tiffany & Co’s most treasured artifacts, and it is Charlie’s main job to protect it. Yet when Jordan Baker meets Nick Carraway she shows off the precious pin stuck casually into her hat. Among the many pieces that have been created specially for the film are cufflinks, a signet ring and the silver handle of a cane, each of which carries Gatsby’s monogram of a daisy, his permanent aide memoire for the reason he is so passionate about the trappings of wealth: because he believes the girl he loves requires them.

Martin’s unbreakable rule has been, ‘Never one feather only. This is not a flapper-themed 21st-birthday party. My aim,’ she says, ‘is to express the true nature of the period through an eclectic combination of things that have a real point of reference.’

This does not mean that she is a stickler for historical accuracy. Part of Martin’s genius (she has won two Oscars, after all, one as production designer, the other as costume designer, both for Moulin Rouge) is how she mixes modern pieces that reference the past in order to make that past seem current. ‘You can’t live your life in fear of the fashion police,’ she says as we flick through racks of delicious dresses by Prada.

‘You have to do what’s right to tell the story and what you believe makes an ethereal moment.’ Like those inflatable zebras in the pool, I say, thinking back to how the eye-popping stripes added even more verve to the party scene. She stops in her tracks. ‘Leonardo was saying to me the other day, “Those zebra lilos didn’t exist,” and I said, “Yes, I have a picture of them.” Here it is.’ (I take the photocopy, glad that Leo and I have at least connected somehow.)

As I leave, I spy Carey Mulligan, slumped on a chair as her final scene is set up, wearing a breathtaking crystal-encrusted Prada party dress with a hideous pair of Crocs. The clock is ticking. I ask her if the Tiffany rock on her finger has helped her to ‘find’ the flighty, beautiful Daisy? ‘I do find myself staring at her ring,’ she replies. ‘I mean, I would never spend more than £100. I would never in a million years imagine actually owning this, so it does throw you into that world. Have you met Charlie who follows me around? The whole notion of Tom and Daisy is that Tom seduces her and wraps her in jewellery. He contains her with his money. They have become a couple because she wanted a great sense of wealth and superiority and he ensnared her with these things.’ She twirls the ring on her slender finger. ‘You feel the weight. In the scenes between Daisy and Gatsby, the engagement ring Tom gave her becomes such a weighty thing.’

In the end, Mulligan will catch her plane. DiCaprio will leave town and my aunt will once again have a gorgeous garden. ‘So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past,’ is how Scott Fitzgerald ended his finest work. As to how Luhrmann ends what promises to be his – and does so in 3D – remains a mystery until next month.

The Great Gatsby is out on May 16. Tiffany’s Ziegfeld Collection celebrates the company’s collaboration with Warner Bros and Bazmark Films on The Great Gatsby (tiffany.co.uk)