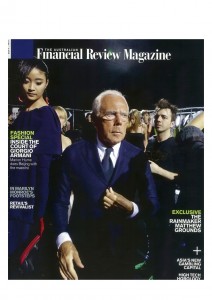

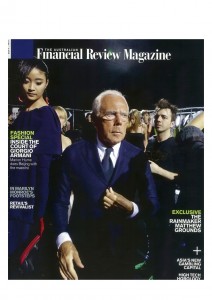

At The Court of Armani

Born in the year of the dog, Italy’s foremost designer is a China crowd pleaser, not least for the well dressed sophistication of his highly wearable clothes. But the succession question dogs the 78 year old all the way to Beijing, where Marion Hume joins him on a night of nights that proves Giorgio Armani is unlike any other of fashion’s living greats.

Austalian Financial Review | August 2012

by Marion Hume

“Are you responsible, compassionate, reliable, honest, pessimistic and anxious?” Giorgio Armani’s ice blue eyes lock onto mine. Who dares ask fashion’s last emperor – his kingdom resolutely independent from the conglomerates that dominate the global luxury landscape – about his personal character? Yet we are in China, where a reporter, born under the year of the tiger, merely wishes to enquire whether the world’s wealthiest designer fits the description of those born under the year of the dog.

This emperor, who has absolute control as sole shareholder of a business worth billions, is shielded by a fiercely protective court. His mandarins – easy to spot because, like their ruler, they don’t wear socks – are stringent about vetting questions in advance. Tabled for today’s interview, taking place in a hotel penthouse 74 storeys above the streets of Beijing at the end of May, is discussion about Armani in China where the group has 289 of some 2125 stand-alone stores globally, with 50 more Chinese openings slated within the year.

There is a beat of silence. Then the interpreter translates the question into the designer’s native Italian (court protocol, as many suspect Armani understands English). “Perfecto!” Armani pronounces. Then he laughs. Then everyone is laughing and so it is that a reporter, distanced from greatness by ample space in which to kowtow, is allowed to stay upright in her chair.

When granted an audience with Armani, whether in the group’s palatial Milan headquarters or anywhere in his dominions, do not expect intimacy. The emperor must maintain distance (unlike, say, Tom Ford, who might start stroking your back). There will be a platoon of people. They will be dressed either just like him (T-shirt, sweater, immaculate casual) or they will ‘work’ his designs in studiously funky ways. The latter is a sartorial shift in a company that used to decree low heels, no earrings, nude nail polish – the change perhaps to semaphore a core brand message of ‘cool’, although the designer himself is 78.

Looking decidedly odd in such an on-trend crowd are the suits. The guy in the tie hand-signalling ‘five minutes to time’s up’ when we’ve only just got started? He’s Armani’s loyal assistant, Paul Lucchesi. The suited and booted guy standing all buff and bristling by the door? His palace guard.

Back in ancient China, it was believed that a man carried the creature of his birth year forever in his heart. Of all the animals in the 12-year cycle of the Shengxiao zodiac, the dog is the most determined. There is no need to ask Giorgio Armani if that is true of him. In 1975, he started a business with cash from selling a car. In 2011 alone, that business achieved a total turnover, including licensed products at retail value, of €6.73 billion ($7.9 billion). The dog is stubborn. When Sergio Galeotti, who was Armani’s partner in business and life, died in 1985, Armani expanded when expected to retreat and runs everything at one of the world’s most recognised brands.

It is written that dogs prefer saving money to spending it. At last report, Giorgio Armani SpA had some $817 million in cash on its books and even Armani’s yacht must earn its keep in charters. To a dog, a well organised home is important. Make that nine private homes, a homeware line called Armani Casa and, in partnership with the UAE property developer Emaar, hotels in Milan and Dubai. But dogs are sensitive, or you might say prickly, given Armani’s less than complimentary comments about other designers’ creations over the years (“molto porno”; “troppo Joan Collins”).

Being born in 1934 makes Armani specifically a ‘wood dog’, the kind that hunts in a pack. Where the emperor leads, others trot behind, even on his annual holiday to Pantelleria, a volcanic speck southwest of Sicily. Apparently, Armani snarls at those he loves the most. In a 2000 interview with Vanity Fair’s Judy Bachrach, he admitted to “verbal violence. And sometimes I even use words, Italian ones – stronzo or cazzo!” Shithead, prick… “That is normal. [Among ourselves], this is what we say all the time.”

This visit to China is not holiday galavanting; it is an international show of brand power – or make that brands, plural. Within the group are Giorgio Armani Privé, Giorgio Armani, Emporio Armani, Armani Collezioni, AJ | Armani Jeans, A/X Armani Exchange, Armani Junior, plus eyewear, watches, jewellery, fragrances and cosmetics. On this evening, the emperor plans to dazzle all those who have received a gilded invitation – accompanied by a little box of nine (Chinese lucky number) Armani Dolce chocolates – with an extravaganza entitled ‘Giorgio Armani: One Night Only in Beijing’.

But overnight success is the opposite to how he got to be here. Along with talent and a singular vision are years of sheer hard work. Armani hails from Piacenza, a northern industrial town far removed from the Italy of La Dolce Vita. Unlike Yves Saint Laurent, born two years after Armani (who was telling his mother how to dress when he was four and was famous by 21), Armani’s childhood stories are not of decorating paper dolls but of hiding in ditches while his home town was strafed in Allied bombing raids. His father worked in the offices of Mussolini’s Fascist Party and then as a shipping manager. His housewife mother could be as hard as nails. It took Armani years to see his name in lights, although for almost as many years since, a vast Emporio Armani sign arcing over Milan’s Linate airport has welcomed visitors.

Armani didn’t design under his own name until he was 40, making him something of a fashion George Clooney (often in Armani on screen), which is to say, old enough to know what to do when fame came knocking. That fame has been burnished through associations with many movie stars at awards ceremonies and in costume collaborations. Who can forget a cocksure Richard Gere, matching Armani shirts, pants, ties in the 1980 filmAmerican Gigolo?

This catapulted an Italian label to international stardom just as Western economies were booming and Young Urban Professionals were wondering what to wear. For men, Armani knocked the stuffing out of the suit. For women, his supple tailoring signalled soft power in a changing world of work.

But that is all known to fashion insiders. What we don’t know, when we show up in China, is the succession plan for a company that directly employs some 5700 people and it’s the scoop all of us are really after. In this imperial tale, there is no little Pu-Yi to ascend to the throne when the current occupant journeys to meet the ancestors, although Armani has two nieces (Silvana and Roberta Armani) and a nephew Andrea Camerana. Instead, two weeks after Armani’s appearances in Beijing, it will be revealed through the Italian daily, Corriere della Sera, that the Giorgio Armani group will become a foundation once the emperor has gone.

This will benefit family members without giving any one of them control and ensure independence, keeping the kingdom safe from far mightier powers such as LVMH. (About a decade ago when LVMH titan, Bernard Arnault approached Armani with an offer few would refuse, Armani did just that.) Such a structure gets around the risks of selling to private equity, which can lead to strange bedfellows, and also protects against the vicissitudes of the stock market.

But while in China, reporters who have travelled across mountains and oceans to get ‘the succession scoop’ do not yet know of this imperial edict. And so it is that an Englishman, an Irishman and a dual nationality British/Australian walk into a hotel penthouse – not the opener to a joke but instead because we English-speaking journalists find ourselves bunched together. (Pressure of time, what with all the French, the Spanish, the Mandarin speakers also interviewing in teams).

We agree the Englishman will be the diplomat: “Can I ask Mr Armani about Beijing and his impressions of Beijing, especially coming back here after four years?” This Aussie will jest about cutting suits big enough for Russell Crowe’s beloved Rabbitohs, while the Irishman, fluent in Italian and in blarney, will watch for the moment to ask “what happens next?”. But do not forget the mandarins are skilled at games of cat and mouse, or shall we say dog-taunt-tiger, rabbit, monkey. An American journalist joins us just as we start, with more questions to be translated, yet with no extra time.

What Armani wants to talk about is clothes. The emperor pontificates, the interpreter waffles on. “He says that with the jacket, he uses more rational shapes, more easy to dress. He says the main difference is not in colours, is not in material, but especially in the structure, the shape.” The penthouse door swings open again and the reporters from across Asia take their seats as we four are ushered out of ours and forward to shake the imperial hand.

Later that day, it is in the subterranean Hades of Beijing’s fake markets, being suffocated by horrid handbags dangling with gewgaws, that the essential difference between the Giorgio Armani brand and almost every other mighty fashion marque slaps me in the face, almost literally. (“Look lady, best LV!”) As I swipe a gawdy Vuitton copy away from my eye line, there are no Armani logos to be seen, not on the cheap clutches piled high on the stalls or among the more convincing fakes I see in private cubbyholes, through doors concealed behind mirrors, or doors disguised as sets of shelves. There’s ‘Hermès’, there’s ‘Fendi’, there’s ‘Chanel’. Fundamentally, Giorgio Armani is a clothing brand with some bags on the side, thus much harder to rip off than those fashion giants which are bag companies with clothes on the side.

While some brands appear to be using China as a shop window (their rich Chinese customers buying abroad where taxes are lower), clothes are different. You might need something tomorrow for a business meeting or cocktail party. The Armani brands sell robustly within China. No numbers are given, but a figure of ‘hundreds of thousands’ of customers gets a nod from Paul Haouzi, who is offered up for the AFRMagazine to interview when it becomes clear that the most senior executive, group commercial director Livio Proli, will not be taking questions.

Haouzi, chief executive Asia Pacific, is a Frenchman fluent in Mandarin, as well as in the English he uses to explain that Armani customers in China “know what they want, understand what fashion is about and want the best. They won’t care too much about price. Armani is a big name and a great product, especially for menswear. And the men here, they really want to look good.”

Training sales staff is key, he says. “The people who serve the customers are not only nice, not only look good, the most important thing is that they are knowledgeable. They have to make sure the person who buys something not only buys the piece, but also buys the Armani experience: the love that Mr Armani has for beauty, for fashion. I want to make sure that our staff are able to deliver more than a piece of clothing.”

Yet while Armani is the king of clothes, paradoxically, the fashion world tends to get much more excited about showpieces spun out by those labels that principally sell bags. Armani does care, personally, that the fashion media shrugs off his wearable offerings as bland when, frankly, where could you go in what comes down the catwalk at Balenciaga?

To examine how good his clothing can be, you have only to take a look at his Australian celebrity clientele. No, not at Cate Blanchett (“In reality she can be very strong, so sometimes you are surprised about this strongness,” Armani says) because she looks good in anything, although it was Blanchett who got Armani to Australia. Not Nicole Kidman either, a natural clothes horse (“Ah, Nicole!”), nor even Russell Crowe, who scrubs up well (“He knows what he wants.”). But recall Armani also clothes the actor’s South Sydney rugby league football team, the Rabbitohs. (In the interview, Armani mimes thighs of magnificent girth accompanied by “molto machile”.) The day the Rabbitohs were fitted is one some of his staffers will never forget, given several players were ‘going commando’. These days, off field, they look impeccable.

As night falls, we are transported at a crawl across Beijing where five million cars have replaced those fabled 10 million bicycles, towards 798 Space, in the city’s Dashanzi art district. Within what was formerly a power plant is the shell of an enormous gasometer (scale: not quite Rome’s Coliseum, but large at 3500 square metres) where a thousand guests mingle for pre-show cocktails inside the perimeter, then are ushered into a stunning theatre-in-the-round. Off-white cushions, bleacher seats, ‘landing lights’ illuminating the catwalk, all echo Armani’s permanent show venue in Milan. American crooner Mary J. Blige is in her dressing room, the models are lined up backstage, all preparing to perform as part of a show which must be costing a fortune. (How much? Who knows, when Armani has to account to no one but himself?)

In this era of the fashion show mega-stylist, Armani does not appear to employ one. Perhaps he does that job himself too. He checks every model before they step out of the wings. Yet while the catwalk is peppered with pieces you’d grab if you could pick what you wanted from a store, on this night, fussed up to look heightened for the dramatic setting, more becomes less. Then, at last, the finale. In the Shengxiao zodiac, dogs are warned: be wary of dragons.

“The pinnacle of the fashion show is a sinuous black lacquered dress around which a spectacular three-dimensional embroidery of a dragon wraps itself, from whose jaws spout not flames, but the lightest of feathers,” is how the final gown is described in an official press release. Shall we just say that the gulf between how fashion scribes express themselves post-show, in private, and what appears in print is often not the same thing. Global reviews are euphoric.

In any case, Giorgio Armani’s true triumph lies not in such travelling circuses. He stands as a style colossus for a quiet elegance that cuts across class and geographical divides. He is a modernist, as Coco Chanel was a modernist, his key contribution to fashion’s lexicon being the calm clothes that promise at least one element of your day will be right. While he has been refining daywear since 1975, it is telling that he did not launch Giorgio Armani Privé, with its sparkling couture gowns, until 30 years later, in 2005.

Included in our Beijing itinerary is a visit to Tsinghua University, where Armani sponsors a program for fashion and textile students. He is here to tell Wen Ya and Wang Yilong that they have been awarded intensive six-month apprenticeships in Milan. It is in the company of these young women, surrounded by their peers, that an emperor becomes mortal, a man with a burning desire to transmit his knowledge to a new generation. Far more animated with the students than with the press, his sense of urgent need – palpable, even through the mire of translation – is to teach that the true power of clothes is to bring out the best in the person who wears them.

Armani leans into the wattage beam of eager young smiles: “I want to say this to all of you: when you design, you should not just think of external things, you should think of internal things. Maybe a woman’s exterior is not so good, so you think of how a woman’s inner beauty can benefit from your designs. This industry needs inner passion.” The lights in the lecture hall dim and some vintage images flash up on a slightly shabby screen. “When the hell is this video from?” snipes one of the press pack, looking up from trawling through emails on his smartphone, only to be plunged back into the 70s.

Then Blondie’s Call Me from American Gigolo comes through the speakers and here they come: Richard Gere, Al Pacino, Tom Cruise, Leonardo DiCaprio, Jack Nicholson, Sean Connery, an older Richard Gere going up the escalator holding a rose. Here comes Michelle Pfeiffer, Michelle Yeoh, Julia Roberts. Armani’s army marches on with Rafael Nadal and a tattooed David Beckham in their underpants, Rihanna in her bra and (surprisingly) Lady Gaga in her clothes. Cut to Beyoncé shimmying in a spangly mini and even the hacks are a bit awed by the punch, punch, punch of it all.

But from where I am seated, light coming off the screen makes Giorgio Armani himself just visible through the blackness. As all those audacious achievements flash up on the screen to the side of him, a silver-haired senior in a tight fitting sweater stares out into nothingness, fine fingers extended in a cathedral of prayer. As a life in fashion plays out before us all, he is marble-still, like a knight on a tomb.

Armani is not like fashion’s other living greats. He is not a designer-for-hire like Karl Lagerfeld who could (although unlikely) spin on his Cuban heels and walk out on Chanel. He is not Ralph Lauren, six years his junior, whose namesake is a public company where one of his sons is senior vice-president. Calvin Klein, who is nine years younger, sold out to the highest bidder and withdrew. Armani has never been one for opulent indulgence like Valentino, who held an unforgettable farewell party and enjoys a luxurious retirement. We know that, one day, the Giorgio Armani Group will become a foundation. But until his last breath, the emperor rules alone.