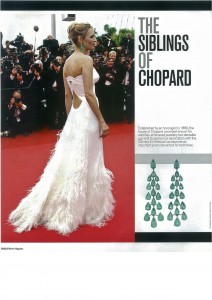

The Siblings of Chopard

AFR | September 2011

by Marion Hume

Could you work with your brother or your sister? For every entrepreneur who shrugs, “Sure”, there’s another who snaps, “not until hell freezes over.” For Caroline Gruosi-Scheufele and Karl-Friedrich Scheufele, the response is, “we’ve shared an office for 25 years.” These sibling co-presidents of the Swiss watch and fine jewellery company, Chopard, are German-by-birth, Swiss by choice, (having braved the rigors of gaining a Swiss passport).

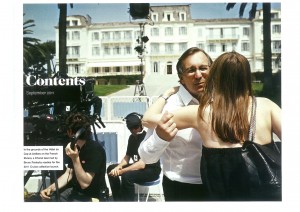

But it would be misleading to imply they have been locked in each other’s company for quarter of a century- during which time Chopard, based in a suburb of Geneva, has grown into a glittering name. “If I am in Geneva for a week, I feel I am not doing anything,” says 49-year-old Caroline, when we chat at the 64th International Cannes Film Festival. “I’m always travelling. My brother and I are very different in character and we are complementary,” she adds.

“Maybe I’m more spontaneous. He would sit more and think and analyse things.” When we meet at the Chopard Headquarters, where about 750 craftsmen are hard at work (the company employs a total of 1,700 people and has more than 120 boutiques and 1600 points of sale), her older brother concurs: “Each of us has very specific areas where we excel.”

The Chopard story is not just a tale of two siblings, it’s a tale of two families; the Scheufeles, German goldsmiths for four generations; and the Chopards, who sold out in 1963 to Caroline and Karl-Friedrich’s parents. Chopard was established by a Swiss horologist named Louis-Ulysse Chopard in 1860 and, when it comes to watches, it turns out 75,000 a year.

I am more fascinated by Chopard’s fine jewellery, launched in 1990. And, more specifically, I’m intrigued by how soon after Uma Thurman’s apperance at the opening night of the Cannes film festival the cascades of emeralds she wore on her ears were sold. (Answer, first serious interest logged within minutes of her appearance, sale concluded the following morning. “And we could have sold them five or six times,” says Caroline of these red carpet one-offs that sold for €270,000.)

By now, it is lunchtime at Cannes. Elegant women, some looking a little the worse for wear after a Chopard-sponsored glittering after-screen beach party the night before, are nibbling on the chilled seafood pasta, served buffet-style on the penthouse terrace of Hotel Martinez. For those whose surnames do not end in Thurman, De Niro, Pitt or indeed Jolie-Pitt, this is where EVERYONE stays during the festival. It’s where you hop into the lift as the doors are closing, say “press seven please for the Chopard lounge,” only then to realise your lift operator is Oscar winner, Adrian Brody.

While Chopard has a presence at the Academy Awards as well as the French Cesars amd the British BAFTAs- and now, thanks to a current push into Australia, is targeting the AFIs as well- it is here at Cannes that the brand has pulled off its greatest coup. While no single commercial brand is particularly associated with the Oscars and the statuette, designed by an MGM studio art director remains almost unchanged since 1929, Chopard designs The Palme d’Or trophy.

Another prestigious Cannes award, presented each year by the biggest star in town to the young actor and actress who show outstanding promise, is called the Trophée Chopard. (Audrey “Amelie” Tautou, and Marion Cotillard are just two winners who have worn “lucky” Chopard jewellery ever since).

These close associations with the film festival have given the brand unequalled muscle on the Cannes red carpet, the scene of not one big night, but twelve. All this promotion comes at considerable cost (how considerable, no one in this private company will say). That it reaps rewards caused London’s Financial Times to highlight Chopard for its soft-sell “masterclass in the art of celebrity endorsement”.

The top floor of Hotel Martinez enjoys a sweeping view along La Croisette to the Palais des Festivals – as long as you can get past the squadron of security guards. Up here, there’s a beauty salon, a nail bar, a chill-out room, complete with both Grey Goose vodka bar and a bank of TV monitors, on which a montage of images of movie star plus Caroline Scheufele, movie star runs on an exhausting loop.

Outside on the terrace, a band, wittily titled The Gypsy Queens provides live music. As a visual centre piece, there is a pair of bejewelled stilettos under glass, billed as “the world’s most expensive shoes”, these the result of a collaboration with Italian shoe-maker, Guiseppe Zanotti. They are in such a small size that when Caroline Scheufele bounds onto the terrace to greet me, I look first at her tiny feet.

I have already decided I like Gruosi-Scheufele, who looks bright as a button, given she is the first (co-) president I have ever encountered whose PA has said, “she never does interviews before noon”. “I’m a night bird, I’m a natural party person,” she says as I take in flawless diamond earrings so massive (5 carat), that on anyone else, I would assume them to be fake. “They have no weight, diamonds have no weight, only gold has weight,” she tells me as she leads me to the VIP area of this already decidedly VIP terrace atop a VIP hotel (by now, I’ve cleared five security checks, three of which are operated by the hotel to keep fans at bay).

Through French doors, I can spy what must then be correctly called the VVVIP suite, where bodyguards protect a client from the Middle East who is being shown an emerald necklace. Of course, I’m supposed to be conducting an interview, not clocking a customer via eyes in the back of my head. But it certainly seems that, in the time it takes me to ask Scheufele a bit about her life in the family firm, a deal is reaching its conclusion. “Is that lady just looking?” I say, feigning innocence. “Buying,” Caroline confirms.

“Sometimes, we sell to the [movie star] who [has borrowed something for the red carpet]. I think it works when the celebrity is first of all choosing what she likes to wear and what she would wear anyway. Then it’s a natural thing. Sometimes, we sell to other clients who like what they saw.”

“But if that lady were a movie star, wouldn’t you give it for free?” I push.“Of course it happens I like to give presents because that would be an honour for the house. It means that people are really appreciating what we do. But they also buy. Jude Law was talking to me yesterday. He said he really liked his watch, and as he’s happy to wear it, he will buy it.” Behind her head, the Middle Eastern lady and her entourage prepare to leave. The necklace is sold.

The Cannes Film Festival has become a truly international gathering of the glam clan. While the late Liz Taylor was a paying customer, the lion’s share of jewellery purchasing power lies now in the Middle East and the BRICS economies, from whence plenty of wealthy customers, with just scant interest in the movies, show up for festival fortnight in their superyachts. There are other jewellers, with pop up shops along La Croisette and selling suites in smart hotels, but what is beyond debate is that Chopard is in the lead here, ever since, some 15 years ago, Caroline Scheufele took herself to Paris to meet with the festival president.

“I said to myself, I’m a cinema lover and that’s how the whole thing started.” That said, her personal taste in film, perhaps similar to that of many guests of sponsors who get the most-prized tickets to evening premieres, does not parallel those movies chosen to screen in competition, of which this year’s Australian entry, Sleeping Beauty was far from the most bleak and disturbing. Caroline’s favourite recent movie? “I liked that one with Julia Roberts in Bali….”

The Chopard HQ, just outside Geneva, betrays no hint of glamour. When you arrive at a cluster of squat grey buildings, the first thing they do is take away your passport. Inside, it is unexpected- that is if you expected the place where they kit out Jane Fonda, Kate Winslet, Carlize Theron, Penelope Cruz to movie-star fabulous. It turns out this place is fabulous, but in a different, hi-industrial kind of way.

After being ushered past enough steel rods, forged in Japan, to support a Shanghai skyscraper (here used to make watches), there is a machine so enormous that it looks like it should have been delivered instead to CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, on the nearby Franco-Swiss border.

So perhaps it’s the scale of the next machine that I like: for in contrast, it is about equal to that of a top-loading ‘nana’ washing machine, (one of those cylindrical ones you had to drag out on wheels and then put the hose pipe out the window). This one is for smelting gold. Some 12 tonnes of it (current spot price, $US52,000 a kilo) is delivered here each year from the nearby UBS vaults. Hardly any jewellers smelt their own gold. Chopard does because, as my guide puts it, “it means we control baking the perfect cake.”

So in goes a bit of copper for a rosy hue, a bit of palladium, a sprinkling of pure silver for strength and then a pile of 24-carat ingots, which are much smaller than those bricks of bullion villains steal in heist movies. The machine heats up to 1,000 degrees. There’s a viewfinder on the top. But what you see through it looks less how you might expect molten gold to look, (my reference; chocolate ads on TV) and more like the view through the Hubble Telescope to Mars. Weird. Wonderful.

Inside the fine jewellery workshop, a craftsman is tweaking the beaks of a pair of jewel-encrusted humming birds, each hovering over a diamond earring. Another holds the empty casement of a dress ring containing a massive 102-carat sapphire secured on a mount full of tiny holes, each of which will be filled with marquise diamonds. Then there’s the strand of 133 perfect South Sea Pearls. When I ask if I might try it on, it weighs me down like a yoke. “We will make the setting very light, with diamonds,” says a master craftsman.

Karl-Friedrich Scheufele meets me in the Chopard museum, which houses 18th century pocket watches and (bizarre this), a fully-stocked bar. While he shares twinkling nut-brown eyes with his sister, his gestures are smaller. Yes, he’s content with running a business in Switzerland, “although our currency is quite strong at the moment and it may become more difficult for us in the next 6-8 months.”

Yes, he’s content with how Chopard is navigating these tough times, “although as we work with our own capital, certainly in our case, we are very careful.” And actually, he is glad his parents did not change the company name to Scheufele, “because we want our product to be the hero. We want people to believe in our brand name, respect it, cherish it. We as a family are not so important. We’re not really so keen about personal publicity.”

What Karl-Friedrich is obsessed by is provenance; a potentially sticky subject if you deal in gems. While the transit of diamonds is now tightly-controlled, it remains relatively simple to smuggle, say, banned Burmese rubies into the Thai supply chain. Karl-Friedrich aims to make Chopard completely transparent, pretty much from rock to ring, and the company is two-years into a three-year process to achieve that. “To be frank, this is not what our customers are asking us yet. But we must ask,” he says.

As to where those customers are, a growing number are in cities he’s still not sure how to pronounce, such as the Chinese coal-rich city of Urumqi. Australia is also on the radar for expansion, where the company hopes to stake a claim to both local custom and the upper end of the tourist market.

But there’s one family question i’ve yet to ask. Did these siblings have any choice of career? Karl-Friedrich pauses. “At one point, I wanted to pick up art as a main study in university. But then I entered into a jewelry apprenticeship and saw that it was also interesting and slowly but surely I found my way to the company.”Caroline has answered the same question at Cannes. “I would have liked to become a singer maybe,” she said, gazing over the Cote d’Azur. “Ballet was also something that I loved. But I had a choice. If my father had been producing lorries or cars, for sure, I would not be there.”