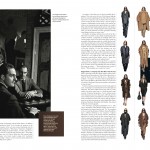

Riding The Coat Tales

Luigi Maramotti has strong views on many things, from a distaste for star designer egos, to resisting the ghettoism of fashion, to cheese. The chairman of the Italian cost company Max Mara shows Marion Hume around the company’s small-town headquarters.

The Austalian Financial Review | September 2013

Reggio Emilia, some two hours east of Milan, is renowned for cheese and for coats. The first has the longer history; rich pastures and traditions being behind wheels of salty treasure that have little in common with ready-grated so-called parmesan found at the supermarket. The family behind the coats remains involved in the making of Parmigiano Reggiano too; both requiring skill and time to achieve the sublime. The label on the coats is Max Mara.

“The fabric we use has been left to lie – the whole idea of seasoning the fabric like you do for a cheese – it’s very slow,” says Luigi Maramotti, a man of quiet yet intense passion who is the company chairman (and who also owns a farm). “A lot of people don’t even know that, at the price per ounce, they might even be paying more for a daily cheese than for the best cheese in the world!”

Is it odd that the head of a fashion powerhouse worth some US$1.7bn should be talking – and with some ferocity – about cheese? Maramotti, a long cool drink of water, also holds strong opinions about high speed rail, education, the “greenwashing” that allows big companies to play at being ethical, as well as the challenges of finding artisans at a time of rising unemployment and austerity yet youthful obsession with being a star. He is also absolutely passionate about art (is that a Gerhard Richter to his left?) and is impeccably attired in a beautiful suit.

Handmade where? Max Mara doesn’t do menswear; the brand celebrates the marriage of technology and the human hand in 23 different womenswear labels. So he brushes the question of the provenance of his suit away, instead indicating what he considers perfection. “These chairs,” he gestures, “designed in 1956, finding the perfect balance, it works, still, but it is not obvious, you need the time, the know-how. ‘Classic’ can have newness and excitement, but perhaps not at a glance….”

At a glance, a Max Mara coat is always beautifully fit-for-purpose. That coats are at the core might go some way to explain why the Max Mara Group has been slow to expand in Australia (while Australia is a luxury source of the merino in so many of those coats…). “I’m not trying to compare to Michelangelo and the quality of the marble, but when you see some great merino, great cashmere or a modern fabric with steel inside which keeps the memory of the shape, it is important,” says Maramotti. “Design being born from respect of the fabric, you do the minimum, you don’t over-design. Shouting about design is not how we convey value.”

No hoopla, no designer taking a bow. Each of the Max Mara lines is created by a team, usually comprising long-term company loyalists, a peppering of emerging talent from London design schools with which Max Mara Group has strong links ( and who, mostly, stay a while, then flee small town life) plus big names such as Karl Lagerfeld; Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana; the Roman, Giambattista Valli and from America, Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez of Proenza Schouler. Yet the latter are only acknowledged when they are no longer working for the company. What is the logic of that? Maramotti says that naming them would only build a platform for their egos, “because it is very unlikely they will negate their ego(s)”. Anonymity instead allows fashion stars to, “forge their expertise with ours and that of our technical teams. I accept that, today, there is a common advantage to use the designer as a marketing tool by which you go for a creative vision of an individual who wants to impose that vision on women….” his mouth forms into a moue of distaste. “What underpins us is a respect for women”.

Reggio Emilia is a company town – Max Mara owns the local hotel, a restaurant and many locals drive or bus to work at the nearby Max Mara campus of steel, glass and several thousand trees. But this is not – Maramotti is emphatic – an outpost. “I measure using not geography, but time. There is a beautiful station near here, designed by (Valencian star-chitect) Santiago Calatrava. I can be in Milan in 38 minutes. How far can you travel in London in 38 minutes? My point is centrality or decentrality is a state of mind…”

Certainly, this has to be the world capital of coats. A morning tour of production has been thorough and impressive. The classic 101801 (known since 1981 by a code number, no catchy names here) is a double-breasted camel overcoat of balanced proportions. A navy cashmere parka with voluminous hood, new this season, will look great for years. In other factories, presumably just as hi-tech, millions of items of clothing for women who want to look up with the times, but not up to the minute, are also made and labeled Max Mara, Sportmax, Pianoforte, Pennyblack, Marella, these joined by Max&Co.,for teenage girls.

The current chairman’s great, great grandmother was a 19th century dress maker called Marina Rinaldi, who has had a label named in her honour since the early 70s. “In everything we do, we resist the ghettoism of fashion. Marina Rinaldi has kept a different thinking in our company,” explains Maramotti, this referring to the welcome fact that Marina Rinaldi is a fashionable alternative for curvier, bustier or taller women who do not otherwise appreciate being siloed into a swamp called“plus sized”. Instead, Marina Rinaldi has seasonal collections, stores on London’s Bond Street, Avenue Montaigne in Paris, a Sydney store in Chifley Plaza. “It is politically correct to say size is not an issue yet size in fashion, it’s a kind of a taboo,” says Maramotti. “I’ve met many women in my life who are interesting and at peace with themselves and not a tiny size.”

Time to get personal. Much of my own wardrobe is Marina Rinaldi – expensive yes, long-lasting too. While of course I don’t believe you have to fit the clothes to write about them (then where would I be?) in a rare subjective assessment, I can confirm that white linen pants last for summers, navy wool tunics can go anywhere and T-shirts keep their shape. My challenge is sometimes I haven’t been able to keep my clothes. I haven’t misplaced any of them, I know exactly why they do not return from hotel laundries. I recall a hotel manager, a big boned woman, offering free nights to compensate my “loss” (her gain). As you don’t need many clothes on an island and I had time to spare, both parties were delighted. I have other examples – enough to argue that larger women love great clothes if they can get their hands on them, but enough for now.

When the founder of the Max Mara Group, Achille Maramotti, died in 2005, he left a business in the care of his three children, Luigi, Maria Ludovica (in charge of product development) and Ignazio (managing director) and this has always been a generational, family story (the company remains private and family controlled). Achille started in 1951, in that post-war surge that saw Northern Italy transforming from an agricultural to an industrial economy. He was much inspired by the female force in his life, his mother, Giulia Fontanesi Maramotti, who, widowed since 1939, had raised four children, funded by her dressmaking school where other young women could gain skills to ensure their independent survival. Achille took a law degree, funded by several jobs including working in a raincoat factory in Switzerland, where he realised that his mother’s craft could be industrialized through a logical system of work. Degree done, he got started, offering useful, attractive clothes to women who had neither the need nor the capital for copies of coquettish Parisian haute couture. The rise of Max Mara is one of classic capitalism, of a man driven by need plus a vision; that creativity could be harnessed profitably to technology. Achille travelled to America where clothes meant the garment industry not a local dressmaker. By the dawn of the 60s, Max Mara production was streamlined to the point that a coat that had taking 18 hours required only two. The company remains is a triumph of technology plus the skills of the human brain and hand (no machine can secure buttons as well as a person can). “Technology helps people repeat best performance for the entire day,” explains Luigi Maramotti. “ Handmade is another legend. It is not true handmade is better than machine. Machines help human beings be the best – you need both. The future, yet the know-how not forgotten.”

Yet the know-how seemingly inherent in the “Made in Italy” label has become complex. “It is a slogan… this idea of democratization of fashion comes from Italy, absolutely. Yet ‘Made in Italy’ can be very frustrating,” Maramotti says, refering to the fact that all one needs to do is put the pieces together in Italy for a garment to earn the prized ‘Made In Italy’ label. “Yet if I design it here, I do prototypes here; that doesn’t count. The central point is, are we, in Italy, capable of keeping alive a heritage that goes back centuries, to the Renaissance, the workshops for ideas?” Another challenge is manning those workshops (with women, the majority of employees). About 20 people in Reggio Emilia retire or relocate each year yet as Italy stumbles through recession, there is no line at the factory gates, despite The Max Mara Group working with the Italian public sector to fund skills training. “This becomes anthropological,” Maramotti muses of the paradox of high unemployment and the lack of apprentices or skilled workers. “You see a lot of young people dreaming of doing things that are much less relevant which they think are better. The values are not perceived correctly. We fight against the perception of ‘blue collar’. I don’t think the major issue is the salary.”

Hardly a casual chat this, for the next subject is sustainability, Maramotti being no fan of external pressures applied by advocacy groups. “There is an entire marketing on these ethical balance sheets,” he sniffs. “I have always opposed this because I prefer to do what works for us. Our power comes from hydro energy, but you don’t make a manifesto, you do the right thing, full stop. The moment it becomes a marketing tool, you are doing something that, ethically, is debatable. I prefer coherence. I know that coherence is boring. Consistency is boring too. But that is the case here.” He warms to the theme, “Some people see a society in which consumption is reduced to a minimum. But because I was trained to look at creativity as part of the growth of an individual, this vision of reducing consumption, making nothing, it is, in a way, offensive to the human intellect. So we have to find a way where we don’t kill ourselves with a model which is sterile.”

Of his own role, of the boss who inherited the top job, he is thoughtful too. “Never separate privileges from burdens, you are just born there, and you have to take what that means,” he muses. “The point is, what are you going to do with that? Absolutely I am privileged. I can think, I can do things. Does that bring responsibility and burdens? That is the question.”