Diamonds That Are Not Forever

A mining company produces Australia’s ultimate raw luxury: pink diamonds. Marion Hume visits Jaipur and Antwerp to discover why the fine jewellery world loves Rio Tinto’s rare gems.

The Austalian Financial Review | March 2013

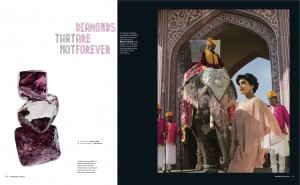

Half a century has passed since the famed fashion maven, Diana Vreeland, declared: “Pink is the navy blue of India”. Yet you can’t go to Jaipur in 2013 without the phrase passing through your mind. It isn’t just the famed pink city, it is the tunics of the guards, the dress worn by Bollywood star Pallavi Sharda, even the elephant’s trunk has a touch of pink. This is because a famous fashion photograph, originally taken by Norman Parkinson, inspired another photo shoot, commissioned by Argyle Diamonds, to tell the story of India’s new love affair with pink diamonds.

The necklace Sharda is wearing is spectacular, 100-plus carats, of which more than a few are very precious pinks. Pink diamonds comprise about 0.03 per cent of global diamond production. Almost all of these come from Rio Tinto’s Argyle mine in Western Australia where, in turn, less than 0.01 per cent of production is pink. In turn once more, 1 per cent of that 0.01 per cent are the finest “fancy pinks” destined for some of the world’s most costly jewellery.

Every year, about 12 million tonnes of Australian earth is shifted in search of diamonds, of which the rarest pink ones, all together, would rattle around in a teacup. It is these that the world’s top jewellers most desire yet have no guarantee of acquiring. Since 1984, the somewhat secretive Argyle Pink Diamond Tender, a moveable feast which tours international cities before the auction takes place by sealed bid, has caused considerable excitement; that is, if you are among the few hundred people worldwide who even know it is happening.

The 2013 tender, of less than 60 stones, is likely to tour from Perth to Hong Kong, Tokyo, New York and beyond – the diamond world does like to be rather cryptic about specifics. Bidders such as Graff, Tiffany & Co, Calleija and Moussaieff face competition from the likes of Bollywood jeweller NiravModi and China’s Chow Tai Fook.

The world’s top jewellers have seen interest in pinks soar among their wealthiest clientele, which is somewhat inconvenient because the supply will probably be exhausted by about 2020. For years, there have been murmurs that the only consistent source of pink diamonds was coming to an end. Technological advances mean a shift from open cast to underground mining at the Argyle mine is possible, with diamonds buried as deep as 450 metres soon to be accessed by a honeycomb of funnels. But they can’t keep going to the centre of the earth.

The luxury world makes many claims to “rare”. Yet pink diamonds truly are. Their hue is not a result of impurity; it’s instead due to extreme pressure beneath the earth’s surface and geologically freaky conditions long before dinosaurs walked the earth.

Nirav Modi of Mumbai leads the field of what to do with a pink. His Golconda necklace was sold for US$3.6 million at Christie’s in 2010. Lightness is the leitmotif of this third generation jeweller. He has worked out how to almost remove the necklace part of a diamond necklace, which is to say, even the links are made of (white) diamonds. “The metal is less weight than the diamonds,” he says of creations that slither like mercury. The stars in each piece are pink but of different hues. “It’s not about getting every single stone to be the same, homogenous colour. With white diamonds, it is all about the clarity.With fancy pinks, it is the intensity of the colour. In fact, the appeal is the range of colours, from a pale pink to a purplish pink, then there’s candy pink. Some are this gorgeous bubble gum pink – except, saying that, it does not sound like a wonderful colour. In diamonds, it is. You need to look at it.”

Modi points to a delicious pink: “Look at that.You don’t often see a colour like that.” As for style, he aims for “modern, not trendy. If you look at your photos 20 years ago, you probably wore bell-bottoms. You cringe at that. You can’t do that with jewellery.”

Pinks are Australia’s ultimate raw luxury, yet the story of their discovery is a grubby and gripping tale of men sporting facial hair and stubbies. They drilled, they dug and on October 2, 1979, they discovered they were literally standing on top of the richest pink diamond deposit in the world.

Nik Senapati, Rio Tinto’s managing director for India, has been with the mining giant for 31 years. A geologist by training, he recalls the “Eureka” day in 1979. “There was elation. It doesn’t happen overnight. But the initial discovery, especially for the geologists who did it, was amazing. Most geologists in the world – I would say 99 per cent of geologists in the world – never discover anything.” Senapati sees Argyle as a very Australian story. “That perseverance; the geologist who was leading at the time, went out and said: ‘well everybody’s looking here, I’m going to look there’.”

Senapati loves diamonds, in a geologist’s kind of way. “A rough diamond formed 150 kilometres down in the earth, transported to the surface in its beautiful crystal form,” he muses. “To hold that. Maybe they should just leave them as beautiful roughs.” Since Argyle, no other consistent source of pinks has been found. So given a diminishing supply by the end of the decade, should the wise man stockpile? “I don’t think you can talk of a stockpile when the entire production since it began wouldn’t fill a glove compartment,” laughs Senapati.

Although the vast majority of all diamonds are cut and polished in India, the largest,most stunning pinks go to Perth. But first, the majority of all rough diamonds, however valuable, take a trip to Antwerp for initial sorting and valuation. While India is the leading nation for diamond cutting and polishing, little Belgium, home of Tin-tin and Dries van Noten, is the rough diamond trading centre of the world. It is in Antwerp that we find Jean-Marc

Lieberherr, Rio Tinto’s general manager for diamonds sales and marketing, in a dull office in a dull building with double door airlocks and shoe mirrors. Security is tight.

Lieberherr, a marketing man, formerly with LVMH, was headhunted. “I knew absolutely nothing about diamonds,” he says. “I started thinking about a mining company producing the ultimate luxury, and a wonderful pink diamond business asking to be developed. The whole concept of marketing and branding is to build a system. But to have this fantastic product which is effectively not marketed at all, it’s really just a joy.”

Diamonds were once marketed brilliantly. De Beers is a tiny chip of the monopoly it once was. Back in the days when it controlled a global cartel, the company needed a slogan that expressed romance and yet would also inhibit the public from reselling. The Mad Men of Madison Avenue came up with “A Diamond Is Forever”, and at a stroke, tiny crystals of carbon became synonymous with wealth and with love.

“Diamonds are forever in that they carry emotions in a timeless manner from one generation to another,” says Lieberherr. “But all the great stories there are around diamonds aren’t told.” What he means is that the old evil stories (blood diamonds, absolutely nothing to do with Argyle and no longer true of 99 per cent of diamond production today) still linger. “Think about the history that goes back billions of years. The chance of it coming up to the surface, people finding it, the impact on the communities. Not one natural story is as exciting as the diamond. We need to start marketing the diamond story a hell of a lot better.”

When it comes to underselling, Lieberherr makes the comparison with the vast land from which pinks hail. He believes Australia is a great brand and that our diamonds can make it even stronger, if we get the narrative right. “I would start with the fact that it’s a world in itself, so how can you live on this planet and not know it?” he suggests. “It’s a very intense place, in terms of its colours, its nature, its landscapes, its dangers. Then I’d talk about the people. I’d develop a brand around Australians being very genuine; their friendliness, their resilience, their resourcefulness.Then I’d probably go to the treasures of Australia, and go to ‘the most expensive substance on earth is here below the surface of Australia, and it’s Argyle pink diamonds’.”

But even for the brand man, isn’t there a conundrum in marketing a diminishing resource? “I think the Argyle pink diamond brand has fantastic potential,” Lieberherr says. “When you think of the awareness it has for anyone who has any interest in jewellery or in diamonds, they know how expensive they are, how rare they are. And that’s been built from what is effectively a tiny, tiny production. “What I dream about is the Argyle pink diamond could become a fantastic jewellery brand, also a watch brand, so that in 50 years time, it’s still there … Argyle the brand will survive the mine. The brand will be about Australian luxury.”